|

| Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society Home : Tredyffrin History : Industries Map Use the links at the left to return to previous pages. |

Tredyffrin History Digital ArchivesAn Introduction to Mills |

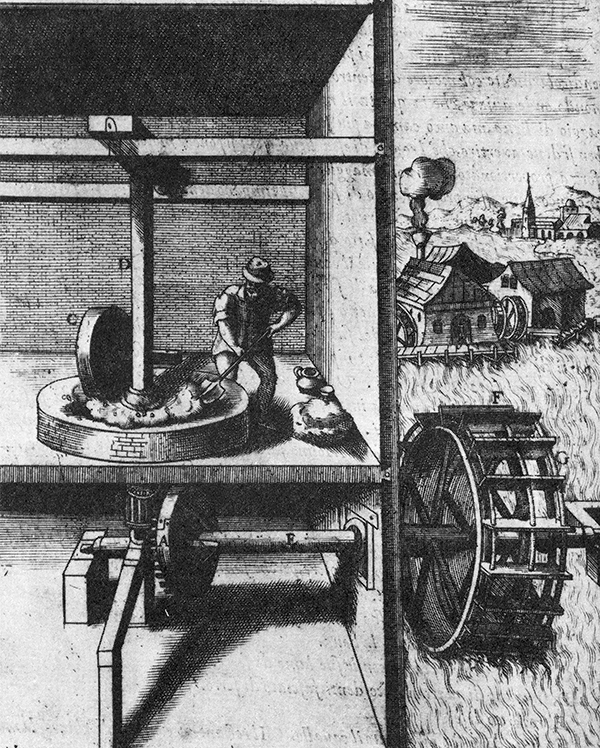

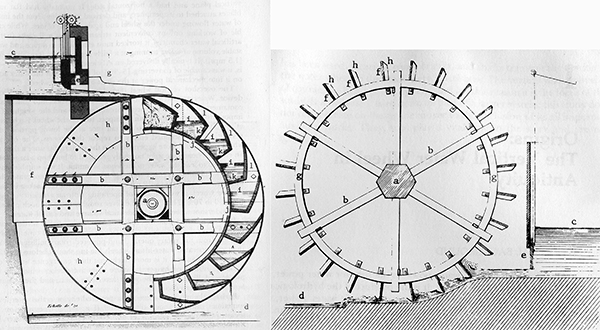

Drawing of wheel from ‘Stronger than a Thousand Men’, by Terry S. Reynolds, John Hopkins University Press, 1983.

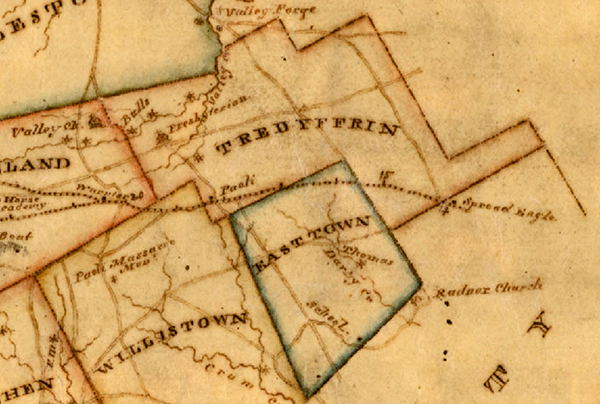

Melish-Whiteside Map of Chester County, 1822, courtesy of Pennsylvania State Archives

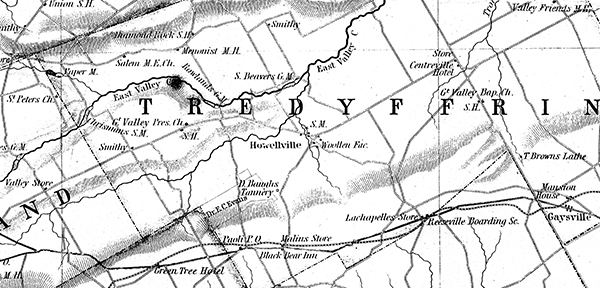

1847 Map of Chester County, courtesy of Pennsylvania State Archives showing various mills

|

Prior to the ready availability of coal and steam power, water was the primary source of power for mills and other industries in Pennsylvania. Even after coal became abundant water-powered industries continued for many years. Tredyffrin had 11 mill sites, some with a very long history. In the 19th century some of these mill sites were converted to be used for manufacturing. Two tanneries also existed in the township and these are also briefly discussed. The quarrying industry will not be described in this article as has been the subject of articles in the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society Quarterly. The Technology of Water WheelsWater-driven mills have been in existence since Roman times or earlier. There were over 5600 flour mills in England at the time of the Doomsday Book (end of 11th century). In the colonial period there were two main configurations of vertical water wheels in use – the undershot and the overshot wheels. In the overshot wheel it is the weight of water entering the wheel at the top that powers the wheel. In the undershot wheel the force of water on the bottom of the wheel causes the rotation. | |

Drawing of waterwheels from ‘Stronger than a Thousand Men’, by Terry S. Reynolds, John Hopkins University Press, 1983. | |

|

The overshot wheel was the more efficient of the two types but required the engineering of a water drop of at least 9 feet so that the mill stream could enter at the top of the wheel. In Tredyffrin that elevation change was difficult to engineer in the Great Valley but was practicable on the hills at the sides of the Valley. Later the breast wheel was invented which was a combination of the two mechanisms of action. Water was directed at the lower middle of the wheel providing force through both the momentum of the water and its weight. Iron breast wheels could approach the efficiency of wooden overshot wheels. Efficiency was also improved by the development of turbine wheels in the 19th century. Types of MillsGrist Mills – the conversion of grain to flour was an integral part of agricultural communities in the 18th and 19th centuries. It is not surprising that a grist mill was built soon after farming was initiated in the Great Valley. The flour was usually packed into barrels for transportation. There were local coopers who would have made the barrels, notably the Ivester family. These mills ranged from small operations used only by a farmer and his neighbors. The miller was usually paid by taking a percentage of the flour, the “miller’s toll”. The larger merchant mills purchased grain and sold the flour on a commercial basis. A store was sometimes associated with these mills supplying local residents with essential items. Saw Mills – the water-powered saw mill was developed in the 11th century. In Tredyffrin it is surprising that there was enough local timber available to keep the saw mills in operation into the second half of the 19th century. |

|

|

|

|

A 19th century sawmill located at the Daniel Boone Homestead, Berks County. Photograph by Mike Bertram, 2006. Fulling Mills – the mechanism of fulling mills consists of water-driven hammers. New cloth folded over frames and then pounded by these hammers to tighten up the weave. Both old and new cloth were treated with Fuller’s earth and then beaten to extract stains. Fullers usually dyed the cloth. Tilt Mills – these mills consisted of a heavy hammer that was raised by the water power and then dropped by gravity after a cam ran over the shaft. These mills were used for manufacturing metal implements such as scythes. Oil Mills – Edge mills were used for crushing plants for oil, sugar, pigments, tannin, & mortar. Plaster Mills – these were also edge mills but used to crush stone such as gypsum for mortar. They could also be used for crushing limestone. | |

|

Woolen & Cotton Mills – in the 19th century water-powered spinning and weaving machines were invented. A number of existing mills were converted to process wool and cotton. In the second half of the century the mills were often converted from water to steam power. Bark Mills – these edge mills were used in the process of extracting tannin for tanning. Clover mill – this mill separated the seed needed for planting from the clover itself. Rather than being trod by horses or flailed by hand, which created obnoxious dust, harvested clover was brought to the mill. The millstone rasped the clover seed, vibrating screens took out straw, and fanning machines blew away chaff. Historical Maps showing Mill Locations | |

|

The above map shows four mills designated by stars. On the main branch of Valley Creek starting in the west of the township is St. Peter’s Mill (owned by John G. Bull, hence the ‘Bulls’ on the map), Great Valley Mill, and Chesterbrook Mill. Howellville Mill is shown on Crabby Creek. | |