|

|

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society Home

: Document Collection Home

Use the links at the left to return.

|

Document Collection |

The Lancaster TurnpikeThe Fifth Ramble |

|

A roster of the taverns within this distance is perhaps best given in the language of a unique toast, a favorite with the hardy teamsters sixty years ago: “Here’s to the Sorrel Horse,

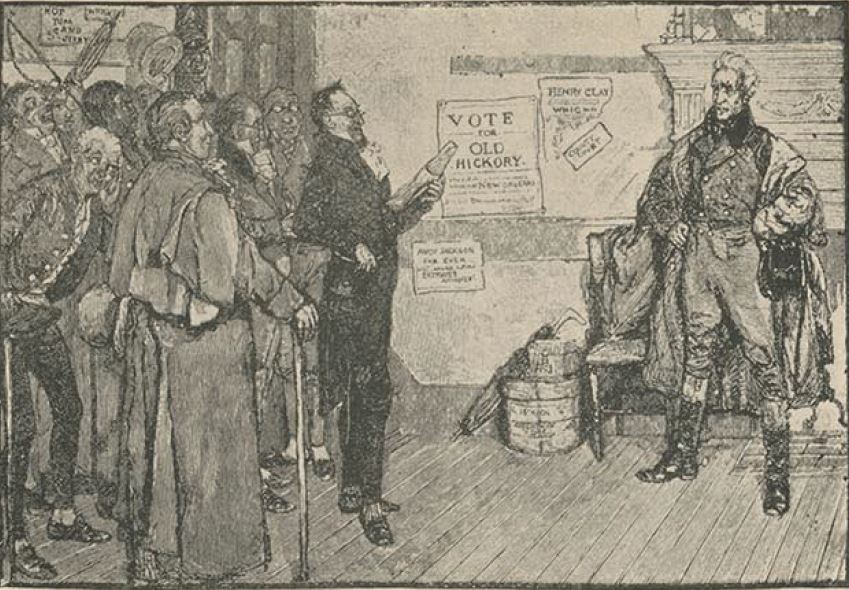

Should this sketch fall into the hands of the few old stagers who are yet alive it may recall a kindly thought for old Joe Pike, who was credited with its authorship. Of the above Inns The Sorrel Horse stood at the lower end of Wayne today. It was a “wagon-stand,” where teams stopped. The Unicorn, at the intersection of the turnpike and the old Conestoga road, was a colonial Inn, known on early records as Miles’ Tavern. It was a Tory house during the Revolution, and was destroyed by fire in 1872. The newer Spread Eagle, a large building erected in 1796, stood near the fourteenth milestone, on completion of the turnpike replacing the primitive structure, an illustration of which forms our frontpiece. This was a “stage-stand” of the first class, which, under the able management of the Siter family, became one of the most noted roadside Inns in the country. On account of its salubrious situation it became at once quite a refuge for the representatives of foreign powers and members of our Government during the summer months, this being especially the case at the outbreak of the yellow fever scourge in 1797-8. As this was strictly a first-class Inn and catered only to first-class custom they charged accordingly. We quote from an old advertisement of 1807, viz: MEALS These prices it seems were high enough to deter any teamster, drover or any other undesirable guest from stopping at the Inn. The reason for the discrimination in price being that they were obliged to prepare meals for the full stage whether travelers came or not. The old Inn after passing through many changes of ownership and uses was finally purchased by Mr. George W. Child’s, of Philadelphia, and torn down in 1887 to make way for modern improvements. Passing up the hill at the northeast corner of the Valley Road, about three hundred yards east of the fifteenth milestone, where now stands a fine suburban residence, was formerly the Lamb Tavern, whose host catered for the entertainment of drovers and butchers. It was erected in 1800 by George Reese, who afterwards became High Sheriff of Philadelphia County. The house, under the Lewises and Klingers, always enjoyed a good reputation among the traveling public. The next Inn, just west of the fifteenth milestone, The Stage, was not what the name would seem to imply, a “stage-stand.” This house also dates back from the early part of the century; sixty years ago, when under the management of Col. Alex. E. Findlay, the Inn gained notoriety as a “Militia House .” Here on Glassley Commons the Annual Cornstalk Musters were held. The next house in order is The Spring House, just opposite the water tank In Berwyn. This tavern was usually known as “Peggy Dane’s,” from the name of the old woman who long presided over its fortunes. It was a “waggon-stand” of good reputation and in later years the porch became the favorite place for country vendues. Just west of the sixteenth milestone we come to where The Drove formerly stood, opposite the deep cut north of the railroad. At first it was what the name implied, viz.: a drive-stand, but in after years it became of unsavory reputation and many gruesome tales are told of emigrants and travelers who were allures into the house, then drugged and robbed, as well as beaten and turned out on the road penniless. Brawls were of frequent occurrence, and culminating in the murder of Nathan Reed, an affair yet in the memory of some older residents. A quaint hip-roof house at the corner of Valley Road has in its time done duty as a parsonage for the Radnor Church, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Boarding School, a Mathematical Academy, and as a country store.  Devon Stables Half a mile west brings us to an old stone house, uncanny in appearance, the very semi-circular windows in the third story seeming to be half-closed eyes of evil. This was formerly Prissey Robinson’s Blue Ball Tavern, and of the tales current in the neighborhood about the house and its weird owner a volume could be written. Catering to the lowest dregs of humanity who frequented the turnpike, quarrels and brawls were always rife, and the many stories of mysterious disappearances seem to have found confirmation in 1877, when the workmen on the railroad unearthed a number of unconfined human remains in the old tavern orchard. A characteristic anecdote of old Prissey is told. When in the early days of the State Railroad a locomotive struck her heifer and killed it, she demanded compensation from the State Canal Collector at Paoli. Her request was curtly refused with the caution to keep her cattle off the track in the future. Prissey vowed vengeance, and on her return home took the tallow from the heifer’s carcass and spread it on the rails the first dark night. This was in the days before locomotives were supplied with sand boxes, and as a consequence the train remained there until morning, when the cause was discovered. It may be added that Prissey’s claim was paid before the day had passed. In the little valley, directly south of this old Inn, may still be seen a part of the original Blue Ball, on the Old Provincial Road, the first Inn opened between the Schuylkill and the Brandywine. In 1730 it was known as the Half-way House, and from 1741 to 1752 was kept by Thomas McKean. On our road west we come at the next crossroads to what was another “wagon-strand,” the Black Bear. Nothing of this Inn remains except the old tavern-pump, which still serves its purpose. The next point of interest is a massive stone house at the eighteenth milestone, formerly the General Jackson, a “stage-stand,” catering for the same class of patronage as the Paoli, a few hundred yards above. The rivalry between the two houses, which were kept by the brothers Randall and Joshua Evans, was very great, and many anecdotes are still current as to the means taken by one to outwit the other. The Jackson in early days was known as “Lodge-stand,” from the fact that here a Masonic Lodge, “Farmers, No. 183, A. Y. M. ” for several years dispensed Masonic light and charity until it succumbed to the anti-masonic craze of sixty-five years ago. The Paoli, under the management of Joshua, became a power in the community as well as a representative American road side tavern. For years the Inn was a political center - in addition to being the polling place for five townships. On important elections it was thought nothing to dispose of from two to three barrels of whiskey to the thirsty voters, besides quantities of cider, cherry bounce and other liquors, of which no account was kept. Volumes could be written of the traditions and customs of the Old Inns on the Lancaster Roadside, their scenes of life and activity forming an ever-changing kaleidoscope. But their day is done, and hosts and guests, the actors have, with few exceptions, long since passed away.  Election Returns, Paoli Inn, 1832  Mill on the Crum |